This post was written by Marie Castelli, BackMarket and Orla Butler, EEB.

On 20 April, the battery regulation trilogues kicked off. What are trilogues? These interinstitutional negotiations bring together the European Council and the Parliament, with the Commission as mediator, in this case to discuss the final text of the new regulation on batteries. We reached out to MEPs as a campaign to encourage them to keep their ambitious stance ahead of the technical discussions that took place last week as part of the trilogues.

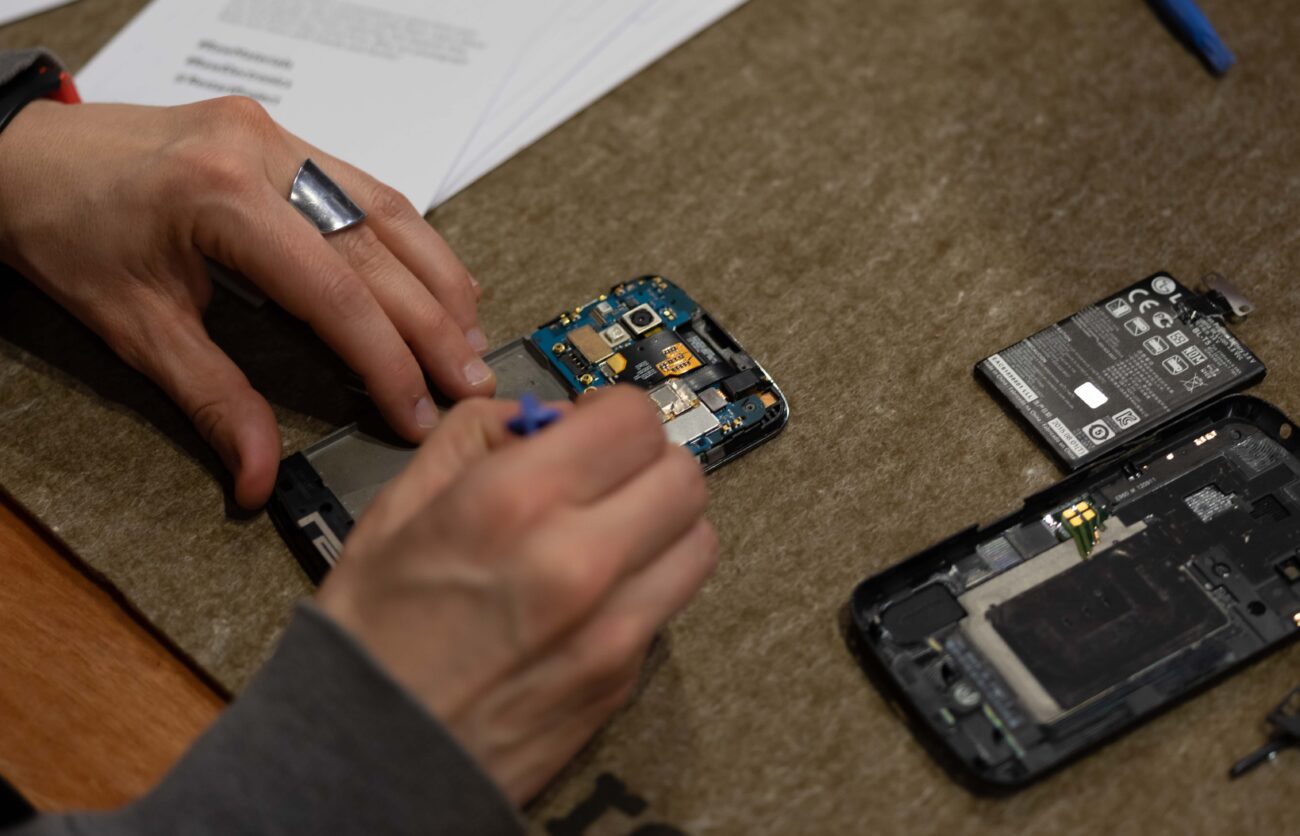

Tough regulations on batteries are key to extending the lifespan of portable electrical devices, hence reducing their environmental impact, and boosting repair and refurbishment jobs in the EU. The devil is always in the detail when it comes to regulations – and in the case of batteries, the way “Article 11” of the regulation will be agreed upon is decisive, as it deals with battery removability and replaceability, a key factor in our ability to repair our devices.

The Parliament adopted an ambitious position in March ahead of the trilogues, in line with its other demonstrations of support for the Right to Repair. With this in mind, we urged MEPs to stick to their original position when discussing Article 11 with the Council and Commission, as the Council’s position in particular was weak and full of loopholes.

As we reminded MEPs, some points in the Parliament version of the regulation are particularly important, and need to be maintained.

Firstly, we flagged the mention of replacement with ”compatible” batteries, instead of ”similar”, as referred to by the Council. ”Similar” would force independent repairers and refurbishers to only use batteries from original manufacturers. Most of the time, these original batteries are not available, or are at discriminatory prices. Therefore, this would lock the repair market by putting it in the hands of manufacturers. As long as functioning, safety and performances are not affected, as the Parliament has said, compatible batteries must be allowed.

The Parliament’s text also mentions that batteries ’shall be available as spare parts of the equipment they power for a minimum of 10 years after placing the last unit of the model on the market, with a reasonable and non-discriminatory price for independent operators and end users’. Discrimination on prices and access to original batteries are a common practice among original manufacturers to monopolise the market, hampering competition and worsening consumers’ experience.

Another key aspect of the Parliament’s version is its statement that ”software shall not be used to affect the replacement of a portable battery or of their key components with another compatible battery or key components”. This is a critical provision, as software is increasingly used to prevent independent repair, for example through part-pairing. It further threatens consumers’ freedom to exercise their right to repair their devices themselves. This is even more important as in the Council’s position there is no mention of preventing software from being used as a barrier to repair.

The Parliament’s text also prevents bundling of batteries to the devices (unless justified) which is another growing practice in device design. Bundling makes battery replacement more difficult – if not impossible – to perform, not to mention its cost! To change a simple battery, which is the most common repair as batteries age over cycles, you need to change an ecosystem of components, or replace a device entirely, as it’s often the case with products such as wireless earphones. Enabling repair by device users would need to ensure bundling is prevented. Finally, it is important to include a provision that instructions for removal and replacement should be available to everyone. More information, more repairs!

On top of those points, we drew MEP’s attention to the definition of a ”wet environment”, mentioned in the Council text. We are concerned that this could be used as an exception to the requirement of making user-replaceable batteries a reality , for example an electric bike required to perform in a wet environment. For those of us who live in places like Belgium, we know how easy it is to find ourselves in this situation! Thus, it’s important that such conditions are not used as loopholes to get out of the regulation’s requirements.

If the MEPs involved manage to get their proposal agreed upon, the framework for batteries (and by extension all our electronics containing them!) will enable easier repairs, less resource use and less electronic waste. The repair and refurbishment sector’s future can truly be influenced positively if this regulation is adopted with an ambitious text, and so we are monitoring this process closely!